by David Fleming

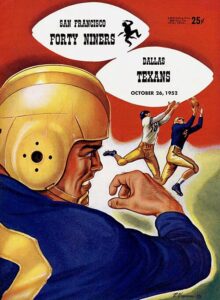

In A Big Mess in Texas, David Fleming reveals the incredible, untold true story of the 1952 Dallas Texans—the most dysfunctional team in the craziest season in NFL history. Read on for a featured excerpt.

The NFL? Have You Gone Completely Crazy?

IN A VOICE DESCRIBED AS A PARTLY MUFFLED ROAR, Clarence Ransom Miller called for an emergency meeting with his company president, a man who just also happened to be his son, Giles. It was a little after 8:30 a.m. on Monday, January 21, 1952, when, inside the offices of Texas Textile Mills Inc., word reached the company’s founder and owner that his precocious middle child was on the verge of investing a substantial portion of the family fortune into something called . . . the National Football League.

The NFL!? Clarence howled.

“Son, have you gone completely crazy!?”

In 1910, with fifteen cents to his name, Clarence Miller left his family’s dusty east Texas cotton farm and walked the train tracks into Dallas to stake his claim. Not in oil, mind you. In overalls. Specifically: dungarees, which, as Clarence loved to say, were the only thing in this crazy world that never changed. By 1952, Clarence had built his little cotton company into the largest fabric manufacturer west of the Mississippi. Now 68, with thick, wavy silver hair and a Lone Star lineage dating back to the Alamo, Miller was considered Southern royalty, a true Texas tycoon. “The Cotton Mill King of the Southwest,” they called him. He had all the trappings of that title: the requisite mansion on Swiss Avenue in north Dallas, dozens of servants, and enough money and power to even consider a run for Texas governor. Seven days a week Mr. C. R., as everyone called him, sported expensive, tailored three-piece suits even though they never fully concealed the telltale thick neck and broad shoulders of an east Texas farm kid.

As founder and CEO of Texas Textile for nearly four decades, Miller lorded over his fiefdom from behind a massive leather-covered mahogany desk that was so daunting (and, let’s be honest, more than a little Freudian) it would have looked utterly ridiculous anywhere outside of Texas. With a dozen mills, six hundred employees, and annual profits well into the millions, from this aircraft carrier–sized platform Mr. C. R. entertained an unusual amount of what one might call “unique” business pitches. Most came from Giles, his middle son, the family’s resident dreamer and schemer who had just been put in charge of TTM’s new investment division.

This being Texas, there were endless asks for wildcatting dough, of course. For a while racehorses and race cars were a thing. There was a real estate phase. A plastics phase. And a politics phase. Money for movie and music producing was a constant. Those were a weakness for C. R., who had supplemented his income when he first arrived in Dallas with orchestra gigs by playing the trombone and cornet. Just a few months earlier, there had even been some cockamamie plan on his desk about a home beverage delivery service, which Mr. C. R. figured was just a convoluted scheme by his thirsty, spoiled offspring to avoid driving to the liquor store.

But, truly, in all his years running Texas Textile, nothing had ever crossed C. R.’s legendary desk as daggum dumb as what his pampered, foolhardy—and dangerously charming—son Giles was considering this morning:

A Dallas franchise in the National Football League.

Talking a mile a minute as usual, Giles explained that he had it on good authority that the struggling New York Yanks were about to fold. As a result, he had been awake for the better part of three days leading a group of Dallas investors who intended to purchase the franchise, transplant it to football-obsessed Texas, and change the course of American sports history—all while showing those damn Yanks a thing or two about how to properly run, and support, a football club.

When he finally paused for a breath, Giles could see that he had managed to make “absolutely no indent for Dad” whatsoever. The old man’s prodigious jowls were growing more crimson by the second. But C. R. refused to say another word, letting his still-unanswered initial inquiry hang heavy in the air between them.

Just what in the hell is going on?!

The NFL?

Son, have you gone completely CRAZY!?

At the time, it would have appeared so. While it would one day grow into a glossy, multibillion-dollar corporation and America’s national pastime, in 1952, when Giles Miller dreamed up the idea of making Dallas the NFL’s first franchise in the South, the National Football League was almost unrecognizable (often, in a good way) from the overly produced, perfectly polished product of today. At the time, “pro football was the haunt of brawlers, boozers and big-time gamblers,” wrote one historian. In the 1950s, the NFL was still very much a ragtag organization perpetually on the verge of financial collapse, pushing a chaotic, bloody, uber-violent, but strangely captivating game still considered by many, including C. R., to be a less respectable form of entertainment than burlesque.

“Mr. C. R. was just apoplectic about the whole thing, about the very thought of his son blowing all that money on something as lowly as the NFL,” said one family member.

After all, baseball was still king in America, followed by college football, boxing, and horse racing. “In national popularity polls, pro football ranked just above synchronized swimming,” wrote Hall of Famer Art Donovan, one of the game’s greatest characters, who chronicled the era in his 1987 memoir, Fatso. “When I played football there? 5 were wild teams, stocked with wild guys, playing during wild times.”

This long-forgotten version of the NFL had everything— except profits. Before Giles Miller spontaneously threw his Stetson in the ring, forty-three other true believers with money to burn had also tried to make a go of it in the NFL.

Thirty-one had gone broke.

After playing for what he described as “a couple of the worst dog-ass teams ever assembled” stocked with “oversized coalminers and west Texas psychopaths,” Donovan sought out family friend and New York State Athletic Commission chairman Jim Farley for some levelheaded career advice on the NFL. Farley, the future postmaster general of the United States, did not mince words.

“Get the hell out of the NFL, son,” he told Donovan.

There’s no future in it, he said.

Farley was, in fact, just echoing the words of the biggest pro football critics of the day: the actual NFL owners themselves. Slimy Washington founder George Preston Marshall revealed to one potential investor that in the thirty years since the league’s founding, a grand total of four NFL clubs had ever shown a significant profit. The NFL commissioner himself, Bert Bell, equated the financial challenges of NFL ownership to balancing an elephant on the end of a toothpick. Before the mountains of television cash changed everything, even teams like the 1948 NFL champion Philadelphia Eagles lost nearly $100,000 a season. They were the lucky ones. Many franchises, including the New York Yanks, the team Giles wanted to spend a chunk of the family fortune on, had lost millions.

In 1952, the NFL was still essentially a Ponzi scheme made up of a handful of fortunate owners constantly searching for easy marks, er, investors, to pay off the massive debts accrued by the long trail of failed franchises that had come before them. In fact, the only reason an NFL franchise was even available for possible relocation to Dallas was that after seven lackluster seasons of failing to garner attention in the media capital of the world, the owners of the New York Yanks had finally thrown in the towel and were about to unload the franchise back to the NFL for pennies on the dollar. The Sporting News concluded that in seven years the only thing the Yanks managed to accomplish was “an unusual ability to blow away a bankroll.” So while the going rate for an NFL franchise appeared to be just $100,000, Giles had to sheepishly explain to his already irate father the deal would actually be contingent on the Millers also assuming $200,000 of what the Yanks still owed on their lease at Yankee Stadium. Which sounded truly ridiculous until Giles explained the original payoff number had been $400,000.

“And just where do you plan to get all of these hundreds of thousands?” Mr. C. R. asked. “Or, do you have a line of credit set up with Fort Knox?”

Deep down, C. R. knew that financing was going to be the least of his son’s worries. The team from New York had three Black players on its roster, and Giles was determined that spots on his NFL team would be awarded on ability only, without regard to race or creed. And the same would go for seating at home games. Even though the NFL had been partly integrated since 1946, this was a brave (if not deeply naïve) stance that was nearly two decades ahead of its time in Texas—and, quite possibly, illegal under Dallas’s ironclad Jim Crow laws. Seating at the Cotton Bowl remained strictly segregated. The rest of Dallas was even worse. In the early 1950s, black families who dared to move out of south Dallas were still regularly having their homes dynamited by the Ku Klux Klan. In Dallas, the rhinestone rodeo buckle of the Bible Belt, mothers, sports purists, and preachers still took a rather dim view of something as depraved as paid football being performed on the Sabbath.

A Big Mess in Texas. Copyright © 2025 by David Fleming. All rights reserved.

DAVID FLEMING is the author of four books and a Peabody-nominated correspondent for Meadowlark Media. During the last three decades at ESPN, Sports Illustrated and Meadowlark, Fleming has been one of the industry’s most prolific, versatile, and imaginative longform storytellers. His unique work has earned numerous national awards as well as a handwritten note from the White House. Fleming is the author of Who’s Your Founding Father?, Breaker Boys: The NFL’s Greatest Team and the Stolen 1925 Championship, and, Noah’s Rainbow. A native of Detroit, and a former D1 wrestler, Fleming and his wife, Kim, live in North Carolina with their daughters.

The post Featured Excerpt: A Big Mess in Texas appeared first on The History Reader.

0 Comments