by Cathy Pegau

Cathy Pegau, author of A Murderous Business: A Mystery, shares with The History Reader how some queer women of means in the United States were able to push boundaries more so than women in poor or middle, working-class families.

Being queer in a heteronormative, patriarchal society has never been particularly easy, and sometimes it was downright dangerous, but even in the first years of the 20th century, if you had enough money, some paths were easier to tread. In early 1900s America, some queer women of means pushed boundaries in ways poor and middle- or working-class queer women couldn’t. Money meant security and stability. Money meant flouting rules with less concern over being penalized. Money meant being able to live your life as you wished. Three women, two who were queer and one who was a great ally, did that with flair.

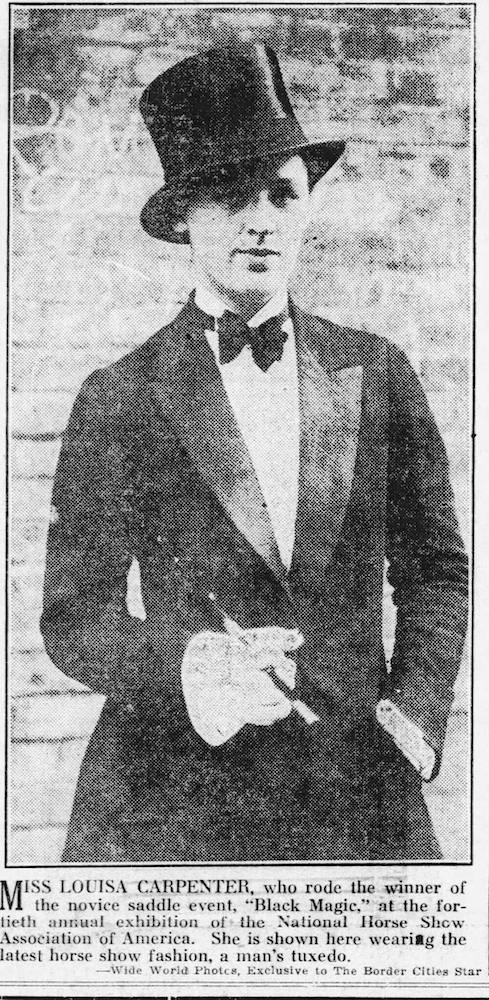

Louisa D’Andelot Carpenter (1907-1976) was an heiress, horsewoman, aviatrix, and philanthropist. She had numerous friendships and affairs with women, often dressed in men’s clothing in public, and eventually entered into a “Boston marriage” with actress Libby Holman. Louisa had little to fear being public about her sexuality; when your family is the du Ponts, one of the richest families of industrial America since the mid-1800s, you can pretty much do as you wish. Her lifestyle may have been unconventional, but she was also quite generous, creating foundations to provide housing for lower income folks and donating money and land to Easter Seals, among others.

Eleanor Randolph Sears (1881-1968) was another queer woman who came from money as a member of the First Families of Boston, also known as the Boston Brahmas. She was a tennis pro and squash player, as well as a consummate horsewoman, traversing the globe to compete. Her penchant for wearing trousers in public drew criticism, but little was ever done about it. While Louisa Carpenter was more inclined to be out, Eleo, as she was known, kept her personal life private in an effort to stave off unwanted attention. She did, however, have great friendships and affairs with a number of women, and lived with a woman later in life who took great advantage of Eleo’s wealth and generosity, one who nearly succeeded in wrenching every penny from her estate.

A’Lelia Walker (1885-1931) was the daughter of Madam C.J. Walker, America’s first female self-made millionaire. A’Lelia was a savvy businesswoman in her own right, working alongside her mother in their cosmetics business, establishing a training school for Walker cosmeticians, and creating marketing campaigns. But A’Lelia was also greatly interested in promoting and supporting the arts, holding dances and soirees at her home. Numerous members of the Harlem Renaissance, artists, writers, and other renowned figures attended her parties. While not queer herself, A’Lelia provided a safe space for people of all inclinations to meet up and have a good time. A very good time. A’Lelia’s acceptance of queerness in her community can only be admired and appreciated.

These three women had the means to live their lives as they wished, but for each queer person with money, there have been millions who have had to fit themselves into a heteronormative world in order to survive. Still, we can appreciate that these women and others like them had to face some societal pressures. They may not have had to hide their sexualities and alliances completely, but in their own ways, they stood up for those who couldn’t be seen in public.

Society has greatly changed in one hundred years and, for the most part, we’ve been able to move out of the shadows no matter our rung on the social ladder or amount in our bank accounts.

Cathy Pegau is the author of the Charlotte Brody historical mystery series and LGBTQ romances with Carina Press. She lives in a small fishing town in Alaska with her spouse, pets, and the occasional black bear wandering through the yard.

The post 20th Century Queer Women of Means appeared first on The History Reader.

0 Comments